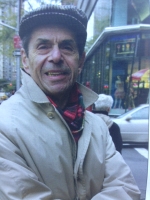

Saul Bennett (d.)

Nothing

In the shack we share

in the woods near the house

my daughter and I convene.

She died four years ago,

almost, suddenly, 24, leaving us,

younger brother, sister. Our children came

less than two years apart.

We moved, my wife and I,

last year, left the density.

The children are in the city.

I do a little consulting

from the house and make

poems in the shack behind.

A good number of the poems are about her,

us, sometimes the five of us.

God doesn't tap my shoulder.

The place has nothing in it,

nothing: stone floor,

cracked;

raw walls;

eaten away foot

wide plank ledge--my desk. I stand.

Moving newspaper soft black copy pencils

without erasers from my old days

I compose, revise in fine point fountain pen

green, harvest,

bury, reluctantly, overripe

darlings, dreaming

out the unwashed shallow window

that won't open. Around,

the box musn't be much

more than six feet. There

we converse in her element. There I feel nothing

comes between us.

Nothing.

* * *

On The Menu At The Asia Food Shoppe, Sunnyside, Queens, 1949

Sounding more sophisticated at mid-century

than chow mein to my mother, subgum became

the minor rage Sundays at Chinese restaurants

situated along the El line in our canton of Queens.

Ordering, in a raised voice, subgum in an eat-out

--you wished to be overheard, of course--

was meant to say, after the War, you were stepping

out smartly in an age when "smartness"

stood for suave, polish, no little derring-do

--picture an early chopper lifting you, say,

from the roof of the RKO Corona, dropping you

at the outskirts (you remembered your camera!)

of some loftier culture. And where is subgum today?

No one has seen it in years, years. I recommend

you question closely--grill it--chow mein, although

by now, I would imagine, chow mein, after interring,

summarily, its upstart rival subgum, in bitter decline

for ages itself, has died somewhere in Queens,

long known, owing to, a surprise to many,

its number of cemeteries, as the "Borough of the Dead."

* * *

Trolley transfer points were wondrous at 5,

binding planets.

Awaiting our connecting car

watching our first trolley shimmy off toward

downtown Jupiter held our winter breath.

Our trolley once was a weathered

crimson below the belt, faded cream upper,

belly button headlight

ingesting an endless tube of gathering duck.

As our our next trolley turtled closer Aunt shouted

"Watch out!" backing us off the hilly

cobbled block.

When the conductor shooshed

the flopping steps down

we were first aboard for the run from Northern Boulevard to Mars!

* * *

About the Author

Saul Bennett (1936-2006) was a loyal member of the Woodstock Poetry Society. He retired to town in the mid-1990s with his wife after serving as president of a public relations firm on Madison Avenue. He'd been "shocked" into writing poetry, as he'd put it, by the sudden death of his oldest daughter. So grief was his first great subject, but in time he wrote about his childhood in Sunnyside, Queens after World War Two. By the end he was finding delight in nature. He published New Fields and Other Stones: On A Child's Death and Harpo Marx at Prayer along with a chapbook Jesus Matinees and Other Poems. His final unpublished manuscript, Sea Dust, included an homage to his favorite poet, Gerard Manley Hopkins, who also wrestled with devastating grief in a world that could still be stunningly beautiful.

(click here to close this window)